Are you looking for resources on preventing gender-based violence? Have a look at our Preventing Gender-Based Violence Resources page.

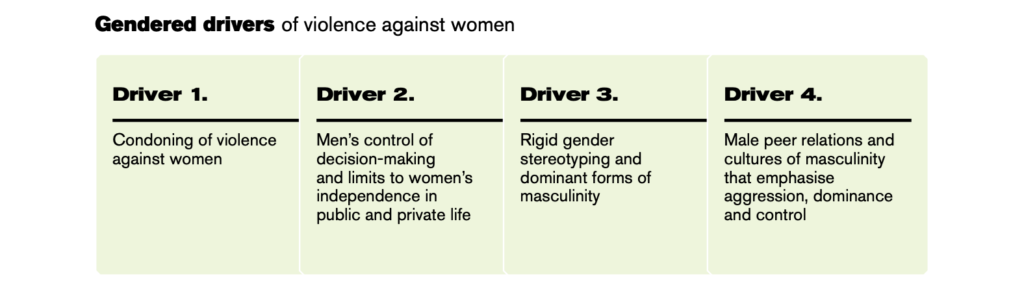

Primary prevention is a health promotion term that refers to preventing a health issue before it occurs. In the context of gender-based violence, this means addressing the underlying gendered power imbalances embedded within societal systems, norms and attitudes that drive violence against women (Our Watch 2021).

WHIN’s prevention practice is based on overwhelming national and international evidence that identifies gender inequality as the cause of gender-based violence. This evidence calls upon organisations and communities to work together to change the norms, structures and practices that create and reinforce gender inequality and gender-based violence.

Gender-based violence is defined as harmful acts directed at an individual or group based on their gender (UN Women 2020). Women’s right to live free from violence is recognised in international agreements as a fundamental human right.

Change the Story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women and their children in Australia presents the evidence base and a conceptual framework for primary prevention work in Australia. All objectives and strategies in the Building Respectful Strategy 2021-2026 seek to address the essential actions laid out in Change the Story across a range of settings and populations.

Learn more about the Change the Story framework here.

Key facts

- In Australia, 1 in 3 women have experienced physical violence since the age of 15 (ABS 2017).

- 1 in 5 women have experienced sexual violence since the age of 15 (ABS 2017).

- Women are nearly three times more likely than men to experience violence from an intimate partner (ABS 2017).

- On average one woman a week is killed by a partner or former partner (ABS 2017).

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women experience family violence at 3.1 times the rate of non-Indigenous women (Our Watch 2021).

- LGBTIQ women can experience unique forms of violence, including threats of ‘outing’, shaming of LGBTIQ identity or – for those who are HIV-positive or taking hormones to affirm their gender – withholding of hormones or medication (Our Watch 2021).

- 36% of women with disability reported experiencing intimate partner violence since age 15 (compared to 21% of women without disability) (Our Watch 2021).

- As many as four in 10 Australians mistrust women’s reports of sexual violence (NCAS, 2017).

Intersectionality

Overlapping forms of discrimination women experience, such as colonisation, racism, ageism, homophobia, transphobia and ableism commonly intersect with sexism and misogyny to increase risk, severity and frequency of violence (Victorian Government 2021). Family violence is not part of any specific culture or community, rather it is the role of power imbalances and discrimination subjected upon people from diverse communities that render them at a higher risk of experiencing serious, more complex violence (Victorian Government, 2021).

WHIN work to challenge misconceptions around violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Violence is not a part of traditional Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander cultures and is perpetrated by men from many cultural backgrounds (Our Watch, 2018). Violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women is caused by deep systemic issues including colonisation, that require specific attention. WHIN acknowledges that as one of the longest surviving cultures in the world, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people successfully managed all forms of relationships for 60,000 years before colonisation (Our Watch, 2018).

WHIN further recognise that the rigid gender norms that drive violence against women are closely linked to and related to the drivers of violence against LGBTQI+ people. Rigid gender norms in society that value heteronormativity (and cisnormativity), also drive violence against trans and gender diverse people and directly play into inequality experienced by LGBTIQ peoples (Pride in Prevention 2020). WHIN’s work focuses on addressing the drivers of violence experienced by women and gender diverse peoples that will have benefits for people of different genders and ensure that everyone is treated with respect. This area of family violence is under researched and greater understanding and resourcing is needed to be directed towards developing an understanding of the drivers of family violence in LGBTIQ communities to effectively target primary prevention efforts (Pride in Prevention 2020).

In the northern metropolitan region (NMR), the number of reported family violence incidents increased from 9,831 in 2018-19 to 10,388 in 2019-2020 (The Victorian Women’s Health Atlas). For current national statistics, refer to Our Watch. For rates of family violence and sexual assault in the northern metropolitan region of Melbourne, refer to The Victorian Women’s Health Atlas that includes a range of health data on the impact of gender upon health indicators, including family violence.

Impacts

Violence against women has wide reaching and long-lasting impacts women’s health and well-being, as well as wider society. For women this includes negative impacts upon mental health, housing, financial security, employment and sexual and reproductive health (Safe + Equal). Gender-based violence further has significant overflowing costs upon the community. In 2015-16, family violence was estimated to have cost Australia $22 billion (KPMG 2016). It is likely that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, pregnant women, women with disability, and women experiencing homelessness were underrepresented in this calculation, potentially adding a further $4 billion to this cost (KPMG 2016).

Policy Context

In the past few years following the Royal Commission into Family Violence in 2015, substantial advances have been made in policy and planning for preventing violence against women across the international, national and state levels. For the Victorian Government this notably includes the Ending Family Violence: Victoria’s plan for change (2016), which commits to implementing all 227 recommendations from the Royal Commission.

Learn more about the current laws, policies and strategies that contextualise work in the northern metropolitan region of Melbourne on WHINS’s Background Papers for the BRC Strategy 2021.

Evidence Base

There are a number of significant frameworks and reports that guide the primary prevention of violence against women.

These include:

- Change the Story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women and their children in Australia (Second edition) (Our Watch, 2021)

- A Framework to Underpin Action to Prevent Violence Against Women (UN Women, 2015)

- Violence Against Women in Australia: An overview of research and approaches to primary prevention (VicHealth, 2017)

- Australian’s Attitudes to Violence Against Women: Findings from the 2017 National Community Attitudes towards Violence Against Women Survey (ANROWS, 2017)

- Personal Safety Survey, Australia (ABS, 2016)

There are currently two national government-funded agencies that support preventing violence against women work and continue to build the evidence base: